Walter Wangerin taught English at UE from 1970 to 1991, and from 1977 to 1985, he was the pastor of Evansville's Grace Lutheran Church. While in Evansville, he wrote a weekly column for The Evansville Press and hosted an evening radio show on WNIN-FM. Wangerin was the author of more than thirty novels, numerous children's books, and a handful of plays, and he received several awards for his short stories and essays. Most of his writing were religious, primarily giving theological guidance on subjects such as marriage, meditation, parenting, and grieving. Other religious books concern the events in the Bible.

Amazon’s website states, “Walter Wangerin Jr. is widely recognized as one of the most gifted writers writing today on the issues of faith and spirituality. Starting with the renowned Book of the Dun Cow, Wangerin's writing career has encompassed most every genre: fiction, essay, short story, children's story, meditation, and biblical exposition. His writing voice is immediately recognizable, and his fans number in the millions. The author of over forty books, Wangerin has won the National Book Award, New York Times Best Children's Book of the Year Award, and several Gold Medallions.”

The Book of the Dun Cow won a U.S. National Book Award in the one-year category Science Fiction. His Letters from the Land of Cancer received the Award of Merit in the Spirituality category of the 2011 Christianity Today Book Awards. The Evangelical Christian Publishers Association awarded Wangerin six Gold Medallions (now Christian Book Awards) in several categories.

Award-winning author, professor, pastor, broadcaster, and speaker Walter Wangerin Jr., 77, died August 5, 2021. He was Emil and Elfriede Jochum Professor and writer-in-residence at Valparaiso University. Wangerin won the National Book Award, The New York Times Best Children’s Book of the Year Award, and several Evangelical Christian Publishers Association Gold Medallion Awards, including for The Book of God: The Bible as a Novel (Zondervan, 1998) and Paul: A Novel (Zondervan, 2001).

The author of more than forty books, Wangerin’s writing career encompassed multiple literary genres: fiction, essay, spirituality, children’s stories, and biblical exposition. He was an ordained pastor in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America (ELCA), speaker for the ELCA’s nationally syndicated radio program, Lutheran Vespers, from 1994 through January 2005, and a columnist for The Lutheran magazine. Prior to joining Valparaiso’s faculty, he served as an inner-city pastor in Evansville, Indiana, for sixteen years. Wangerin was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2006.

In August 2002, Wangerin embarked on a 9-week bicycle tour called “Outspoken for Lutheran Vespers” through eight Midwestern states in an effort to draw attention to ELCA’s radio ministry. He broke his hip in a biking accident as he neared the halfway point and completed the trip in a motor home.

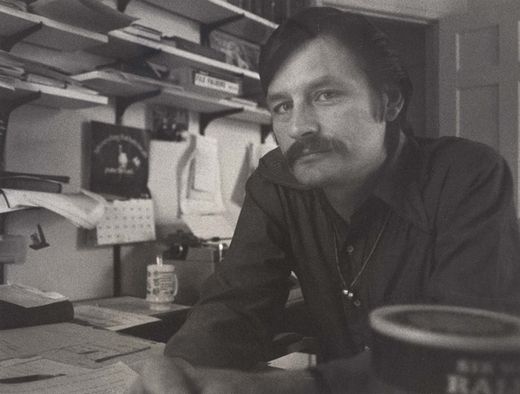

Calvin Kimbrough, Jr. photographed the following picture of Walgerin in 1981 in his office at Grace Lutheran Church. Kimbrough commented, “His wonderful voice still resonates in our hearts!”

Philip Amerson, President Emeritus at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, wrote the following about Walter Wangerin:

“Last week, Walter Wangerin Jr. passed away, and a unique voice fell silent. His wife Thanne (short for Ruth Anne), his family, and a few close friends from Valparaiso University were with him when he died.

I first encountered Walter as a speaker at a conference in which we both participated. A slender man with a handsome, angular face and a shock of dark hair, he stalked the stage like a Shakespearean actor. I thought of the accounts of Charles Dickens sitting onstage in the great halls of England, reading his stories to a mesmerized audience.

Yet Wangerin was neither reading nor sitting. He was performing in the purest sense of the word, weaving stories and concepts together in erudite prose, directing our minds and emotions much as a conductor directs an orchestra’s sounds—now meditative and melodic, now electrifying and bombastic.

We got to know each other mainly through the Chrysostom Society, a group comprising 20 or so writers of faith. Walt usually sat quietly on the margins, stroking his then-shaven chin while observing everything around him with piercing blue eyes. He rarely showed emotion, and when he spoke, he acted as a peacemaker, calming the heated arguments that sometimes emerged from the gaggle of writers. A pastor by profession and calling, he seemed thrilled simply to be in the company of writers.

A few years before, he had written The Book of the Dun Cow. At the time, he was trying to support his family on the salary provided by his predominantly African American church, and his days were filled with counseling, parenting, social work, and the many tasks of an inner-city pastor.

To his surprise more than anyone’s, his first book won the National Book Award in the science fiction category, a prestigious award that propelled him into exalted company. The winners in other categories that year included Henry Kissinger, Tom Wolfe, John Irving, William Styron, and Madeleine L’Engle.

Walt and I became fast friends. I had been working in publishing for more than a decade, and he had many questions about the arcane world of editors, agents, and marketing. He wanted only to write, and had just resigned from the church in order to devote himself to the craft full time. I answered dozens of letters of anguish about the pressure he felt from publishers to modify his style. Editors drove him crazy. They urged him to streamline his “heightened prose” and adopt a more pragmatic tone. Walt would listen to their advice, agonize for weeks, and finally decide to ignore it.

No doubt, staying true to his principles cost Walt a broader readership. For example, his book As for Me and My House contains more helpful advice than a dozen others offering “ten steps for a better marriage.”

Yet he rightly refused to accommodate his natural style to the artificiality of self-help bromides. He chose to subsume some of his most powerful personal experiences into The Orphean Passages, knowing that many readers would miss the Greek myth’s overtones. And in private conversations, I heard from him chilling childhood stories that he declined to write about because of the pain it would cause family members.

Walt knew he was swimming against the tide. He spoke of the “cool pragmatism” of modern literary taste. He sought instead to draw the reader into another world, a suspension of disbelief carried more by music and lyricism than by sense and reason. He once told me in a letter that “a writer hopes for the obedience of a good reader who says, ‘I will enter this world a while, however different it is from my own more familiar expressions of truth.’”

Thousands and ultimately millions of readers responded. The late Eugene Peterson, sometimes called “the pastor’s pastor,” credited Wangerin’s first book with helping to clarify his understanding of the pastor’s life. The Book of the Dun Cow, a fantasy novel based loosely on a tale from Geoffrey Chaucer, stars a rooster and a basilisk, along with such supporting characters as a rat, a fox, a toad, and a melancholy dog.”

|